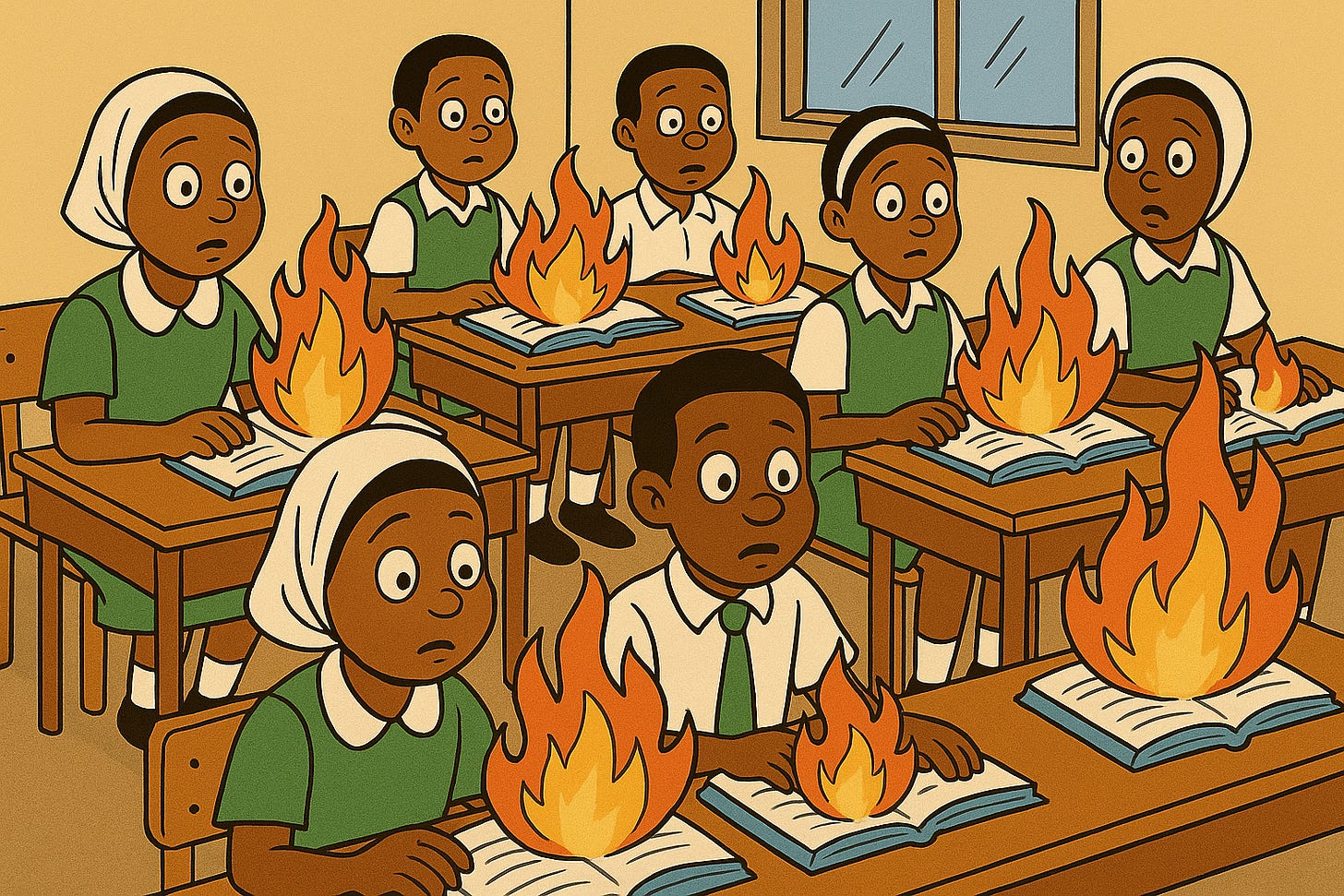

Nigeria deleted its own history

In 1982, Nigeria removed history from schools and replaced it with “social studies.” What followed was decades of lost memory and a generation raised without its past.

When I first learned that Nigeria had no history in its schools, I thought it was a rumour. A made up story for clicks and engagement on social media.

How could a nation so vast, so rich in culture, decide that history didn’t matter?

Then I cast my mind back to my school days in Lagos and then realised what I’d learned wasn’t history but Social Studies.

It wasn’t a rumour…

In 1982, under the new 6-3-3-4 education system, the government removed history from junior secondary schools. They folded it into something called social studies, a curated mix of lessons designed to emphasise the unity of Nigeria as a state. No deep dive into kingdoms before colonialism.

No serious study of the civil war. Just a neat story about the federal union.

By 2009, things got worse. History wasn’t just diluted; it was erased. Under Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, the new basic curriculum eliminated history completely from both primary and junior secondary schools. For over a decade, Nigerian children grew up with no structured history education at all.

The official excuses were almost laughable

Students found history boring. Really? In a land of epic stories, from empires to resistance movements, history was “too boring”? Come on.

Poor career prospects. As if 10-year-olds were choosing subjects based on job markets.

Teacher shortages. If you can train 3,700 teachers to reintroduce history later, why couldn’t you train them back then?

The truth is, in my opinion, those reasons were smokescreens.

The real reason, analysts say, was about controlling memory. The Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) still haunts the nation. Millions died, and the wounds never healed. By erasing history from classrooms, the state could manage what future generations remembered, or didn’t remember, about that painful era.

Think about the damage. A whole generation grew up not knowing their past, not questioning the contradictions of the present, not connecting to the depth of African civilisation before colonisation. And it wasn’t just Nigeria. Across Africa, similar patterns unfolded. Colonisers left us with curricula that glorified them and minimised us. Post-colonial leaders often kept it that way.

Now, in 2025, history is finally back.

President Bola Tinubu and Education Minister Tunji Alausa have reintroduced it as a compulsory subject in primary and secondary schools.

On the surface, it sounds like a victory.

But the real question is: what kind of history will be taught?

Because if it’s not pre-colonial, if it doesn’t name names and confront the truth, then it’s just another managed narrative.

For me, this story is a reminder: history is never neutral. It’s either weaponised to control us or reclaimed to empower us.

In a future post, I’ll show you the real reason Nigeria erased history and why erasing memory has always been a tool of control, from Africa to America.

PAY ATTENTION